Section B. Preparing for and Recovering from Floods

While floods can certainly be devastating events, every post-flood scenario is also an opportunity to investigate what happened and work to eliminate or mitigate future damage. As an elected official, you are uniquely positioned to effect meaningful actions that can reduce future impacts.

You may have heard the term "hazard mitigation" and you may wonder what it means and how mitigation actions can reduce your community's vulnerability to flood damage.

Flood and flood-related hazards have the potential to damage or destroy public and private property and disrupt your local economy and overall quality of life. While threats may never be fully eliminated, much can be done to lessen – to mitigate – future impacts. The concept and practice of reducing risks associated with known hazards is referred to as hazard mitigation.

FEMA Defines Hazard Mitigation

Hazard mitigation refers to any sustained action taken to reduce or eliminate the long term risk to human life and property from hazards.

Before you advocate for change, you'll need to learn about your community's situation (Question 2). You can examine photographs and videos, listen to real-world accounts of flooding and flood rescues, investigate damage scenarios, ask lots of questions of staff and constituents, research existing rules and regulations and review best practices in similarly situated communities.

This section answers some common questions elected officials have about hazard mitigation, what can be done before the next flood to lessen the impacts of flooding, and the types of projects many communities undertake.

6. What is my community's legal responsibility and liability for mitigating flood risk?

Protecting public health, safety, and welfare is one of the fundamental duties of local government. Recognizing and managing floodplains and coastlines is part of the duty to protect people and property. Mitigating flood risk can be challenging, in part because of the common misconception that regulating development creates a direct conflict between the public safety duties of local government and the property rights of individuals.

Local governments mitigate flood risk by controlling land-use and development decisions. This is most often done through planning (comprehensive land use, zoning, special area plans) and development regulations and codes (floodplain management regulations, subdivision standards, and building codes). Regulations and codes are administered though permitting processes that are designed to prevent inappropriate construction or require proper construction or floodproofing of structures in areas prone to flooding (see Question 36 to learn more about requirements for buildings). It is important to note that these regulatory tools are also intended to minimize development or use of lands that will harm other people or properties by increasing flood risk.

Takings

Property owners file takings cases when they believe regulations or other government actions violate their constitutional property rights. The legal basis for these arguments can be found in the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits the government from taking private property for public use without just compensation. The interpretation of the courts through the years has clarified that the Fifth Amendment encompasses more than an outright physical appropriation of land. Under some circumstances, the courts have found that regulations may be so onerous that they effectively make the land useless to the property owner, and that this total deprivation of all beneficial uses is equivalent to physically taking the land. In such a situation, courts may require the governing body to either compensate the landowner or modify the regulation. However, courts have sided with local governments acting to prevent loss of life or property as not violating the takings clause. It is important to remember:

- Communities have the legal power to manage coastal and inland floodplains, and

- Courts may find that communities have the legal responsibility to do so and may actually be liable if they permit development that adversely impacts other properties.

The legal system in the U.S. has long recognized that when a community acts to prevent harm, it is fulfilling a critical duty to protect people and property. Courts throughout the nation, including the U.S. Supreme Court, have consistently ruled in favor of local governments acting to prevent loss of life or property, even when protective measures restrict the use of private property.

"Not all the uses an owner may make of his property are legitimate. When regulation prohibits wrongful uses, no compensation is required."

– The Cato Institute

ASFPM No Adverse Impact: Property Rights and Community Liability: The Legal Framework for Managing Watershed Development

Administrative and management decisions made by local governments must respect property rights and follow the law, but the courts have made it clear that property rights have limits. For example, both state and federal law acknowledge that property owners do not have the right to be a nuisance, violate the property rights of others (for example, by increasing flooding or erosion on other properties), trespass, be negligent, violate reasonable surface water use or riparian laws, or violate the public trust. The courts have also made it clear that preventing projects that could harm others cannot constitute a taking, since the alleged right being violated never existed.

As an elected official, you need to be aware that approving projects or activities that increase the risk of damage to other properties could expose your community to lawsuits. A common pitfall for local governments is that they allow development on a property to avoid a takings challenge by the property owner, only to be hit with a takings claim by neighbors on adjacent properties who are adversely impacted by the decision. Permitting development can damage neighboring properties when water or sediment "trespasses" on the properties without permission. Impacted owners can then sue their communities for issuing construction permits without due diligence. Nationwide, lawsuits by impacted neighbors are litigated as takings with a much higher success rate than takings claims over preventing development.

Legal do's and don'ts of floodplain management

Do:

- Clearly relate regulations to hazard prevention.

- Help landowners identify economic uses.

- Apply identical principles to your government's own activities.

Don't:

- Neglect your duty to manage the floodplain. A hands-off approach is the surest way to be successfully sued.

- Apply regulations inconsistently or arbitrarily or abuse your power.

- Interfere with landowners' rights to exclude trespass of others.

- Deny all economic uses. Consider using Transferable Development Rights in valuable, heavily regulated areas.

Common examples of development that should be examined to avoid causing damage to adjacent properties include:

- Residential or business development that increases flood elevations or erosion

- Development that increases impervious surfaces, which enhance storm flow velocity and volume

- Construction that channelizes storm flow and increases scour of surrounding properties

- Roads that block drainage pathways

- New or upgraded stormwater systems that increase flow downstream

- Structures that block watercourses, which increase flood levels or cause erosion

- Bridges built without adequate openings

- Flood control structures that increase flooding downstream, upstream or across the waterway

The best way to avoid losing in court is to avoid being sued in the first place. Working with landowners prior to development to identify the extent of property that can be developed without adverse impacts on neighbors helps alleviate conflict. This approach is less confrontational than traditional regulatory systems that dictate (often without discussion) when development is or is not allowed. Under this approach, both landowners and regulators have the opportunity to resolve their concerns.

ASFPM has produced numerous publications intended not only to explain these legal issues more in-depth as it relates to flooding but also to highlight important case law that your community's legal counsel may find useful in defending against frivolous suits or being successful in your own enforcement efforts.

While nothing can prevent all legal challenges, a sound, well-planned approach to floodplain and watershed management can help: 1) reduce the number of lawsuits filed against local government, and 2) greatly increase the chances that local government will win legal challenges arising from their floodplain management practices. ASFPM advocates using the No Adverse Impact approach, described in Question 42.

7. My constituents just want things to get back to "normal," the way it was before the flood. Is that so bad?

While there is a natural human impulse, after a disaster, to think about the sunny, comfortable, pre-flood days, doing so ignores the obvious: that "normal" scenario put people and property at risk. You now know enough to break the cycle of "flood, rebuild at risk, and flood again."

You can lead your community by engaging constituents to focus on what's next and the process of recovering better by reducing vulnerability to future flooding. Of course, taking action can be a challenge given so many demands on elected officials, professional staff, and limited budgets.

Many effective mitigation measures are implemented at the community level, where decisions that regulate and control development are made. When you apply effective mitigation planning to your community's approach to preparation and response to floods, and to recovery planning, you can reduce response needs and speed recovery. See Question 12 for examples of hazard mitigation initiatives and projects.

Success Story Connection

Our success stories feature several communities that went beyond simply repairing flood damage and tackled long-term flood resiliency.

However, hazard mitigation can be akin to "tough love." Encouraging your constituents to elevate their buildings higher than the minimum elevation required, set homes farther from the water, or participate in a buyout project is a challenge for even the most well-informed elected official. Sometimes the best solution is the harder choice. Balancing the long-term needs of your community against the short-term needs of individual residents can be particularly difficult when you count on residents for support on a multitude of other community priorities.

8. What is a hazard mitigation plan and why does my community need one?

Does your community already have a mitigation plan?

Check with your floodplain administrator and emergency manager to find out if your community has a hazard mitigation plan, which may go by a different name or be included in a comprehensive plan. Many cities and towns participate in a multi jurisdictional planning initiative, typically led by counties.

As a community formulates a comprehensive approach to reduce the impacts of hazards, a key means to accomplish this task is the development, adoption, and regular update of a local hazard mitigation plan. A hazard mitigation plan identifies hazards that may affect a community and develops estimates of people and property that are at risk. The most common hazards covered by mitigation plans are flooding (from all sources), high winds and tornadoes, earthquakes, and wildland fires. The plans establish community vision, guiding principles and specific actions designed to reduce current and future hazard vulnerabilities.

Hazard mitigation plans help communities:

- Protect life and property by identifying ongoing actions and possible new actions to reduce the potential for future damage and economic losses that result from natural hazards

- Qualify for grant funding, in the pre-disaster and post-disaster environment

- Speed recovery and redevelopment following future disasters

- Demonstrate a firm local commitment to hazard mitigation principles

- Comply with state and federal legislative requirements tied to local hazard mitigation planning

Guidance for Floodplain Management and Hazard Mitigation Planning and Projects

ASFPM, FEMA and many states publish guidance for developing and updating mitigation plans and identifying mitigation projects:

- ASFPM NAI How-to Guide for Planning

- ASFPM NAI How-to Guide for Mitigation

- ASFPM NAI How-to Guide for Infrastructure

- NFIP CRS Coordinator's Manual (activity 510)

- Hazard Mitigation Assistance

9. What actions can we take now to prepare for the next flood?

You've probably heard that when it comes to flooding, "it's not if it will flood, but when." While it's true that many communities are lucky and haven't flooded in decades, flood maps are illustrations of probability.

Section E, The Basics of Flood Risk, explains the "base flood" used by FEMA to prepare Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) and cautions that the term "100-year flood" should not be used because it is widely misinterpreted to mean "once every 100 years." If your community has buildings in the mapped floodplain, the probability those buildings will flood is one chance in 100 in any given year. So why not do what you can now, to get ready for that eventuality?

Plan Your Public Information Messages and Prepare Materials for the Public. Section C describes six priority topic areas that may be appropriate for messages for your community. Once you know about your community's flood risk, you can craft those messages before the next flood occurs. Along with professional staff, you can learn about informational materials developed by others and tailor them to suit your community's needs, which likely include public safety, inspection and permit requirements, and information about recovering in ways to mitigate future damage.

Have Your Departments Evaluate Their Needs Should Widespread Flooding Occur. Some NFIP state coordinating offices produce desk references and handbooks to help local officials charged with floodplain management prepare for and respond to flooding. After you determine if the scope of damage may exceed your community's capacity to perform safety and substantial damage inspections, you may want to pre-plan requesting mutual aid assistance.

Review Your Emergency Plans. An emergency operations plan (EOP) outlines how your community will respond to an emergency, such as a flood, mudslide or hurricane. Your EOP may be part of the county's plan, or there may be a regional plan for emergency response.

Some examples of state guidance include:

- Florida Floodplain Administrator's Post-disaster Toolkit

- Iowa Flood Response Toolkit

- Louisiana Floodplain Management Desk Reference (Chapter 27, Disaster Operations)

Review the EOP with your elected colleagues and department heads. You can ask the following questions to help inform your review:

- What is the role of elected officials, if any? Who is responsible for issuing official announcements, and are messages already drafted, waiting to be tailored for each incident?

- Are the resources and assets described in the EOP readily available, or are we dependent on others for certain assets? Who communicates our needs up the chain?

- Are the responsibilities assigned to our staff reasonable in light of current staffing? Are there key positions that are vacant, unfunded or under-funded?

- Is there potential for multiple or complicating hazards? For example, if an upstream hazardous materials manufacturing facility is flooded, how would that affect us?

- Are there any special considerations you should be aware of regarding utility services? What are the priorities of utility providers to shut off service to flood-prone areas and to return service to critical facilities or important areas?

- Has the plan been tested or executed recently, and are any updates needed to reflect lessons learned?

Review Your Hazard Mitigation Plan. Elected officials are required to approve hazard mitigation plans and each revision (usually every five years). However, annual reviews and status updates of high priority actions are critical to making certain that the plan is being actively implemented. You can gain important background information on your community's flood hazard and vulnerabilities by reviewing the data gathered to support the mitigation actions in your plan.

Keep in mind that access to FEMA mitigation grant funding (Question 10) is tied to the hazard mitigation plan and actions. Your goal when reviewing the plan should be to think ahead and anticipate future, post-flood needs based on existing data, without the constraints of existing financial status, political conditions or financial limitations. What actions might your community want to take in the future, and where? Are those actions included in the plan?

10. What resources are available to help us prepare for and recover from the next flood?

Emergency managers focus on preparing for and responding to a wide range of emergencies. More than likely, you were briefed by your community's emergency manager (or the county's emergency manager) when you first took office. Your emergency manager is your first stop for questions about preparing for floods, what's available immediately following floods and the processes that are activated after the governor declares an emergency or disaster.

Solutions Exist to Support Flood Mitigation Investment. Funding flood mitigation is a challenge, but developing creative local solutions and exploring diverse financing sources to fund mitigation projects can ease the financial strain on communities. Existing federal and other governmental assistance programs can help ease the financial burden for homeowners and community leaders. Communities can leverage local resources to help cover costs as well.

When events exceed state and local capacities, governors ask the President to declare emergencies and major disasters, making available federal resources to help with recovery. Ask your emergency manager to brief you on these FEMA programs:

- Individuals and Households Assistance Program: assistance for some expenses (medical and dental, child care, funeral and burial, essential household items, moving and storage, vehicle, and some clean-up supplies) and items not covered by insurance.

- Public Assistance Program: debris removal, life-saving emergency protective measures, and the repair, replacement or restoration of disaster-damaged publicly owned facilities and the facilities of certain private non-profit organizations; Public Assistance may include funding to mitigate the effects of future disaster (see Question 11 about Section 406 mitigation).

State hazard mitigation officers are typically located in state emergency management agencies. Similar to NFIP state coordinators, who work with communities to fulfill their responsibilities to the NFIP, state hazard mitigation officers are charged with maintaining awareness of mitigation planning and grant programs available from FEMA and other federal agencies, and helping communities access resources that support those efforts.

Other Federal Agency Mitigation Funds:

Federal agencies other than FEMA also administer programs that support hazard mitigation, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of the Interior, Economic Development Administration and the Department of Agriculture. After some disasters, Congress authorizes special housing funding administered by HUD. Check with your state hazard mitigation office or visit the American Planning Association's website for more information on the mitigation initiatives of these agencies.

State and Private Mitigation Funds:

Some states have state-funded programs to support projects to reduce future flood damage. In recent years, some private foundations have become interested in supporting initiatives to deal with specific issues such as climate change and sea level rise (for example, 100 Resilient Cities, pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation). Those funds are not detailed here, but stay aware of opportunities that may arise.

Local Mitigation Funds:

Cities and counties can raise money for flood mitigation themselves rather than relying solely on state or federal dollars. This allows communities to fill in funding gaps, match funds from the federal government (where matching is generally required), and help support state of the art flood mitigation projects. Ways to raise mitigation funds locally include stormwater utility fees or charges, general obligation bonds, catastrophe (disaster) bonds, special levies for a specific purpose (or project) and temporary tax rate increases.

Success Story Connection

One year after Hurricane Harvey, Harris County, Texas approved a $2.5 billion Flood Protection Bond Issue in a special election. Judge Ed Emmett, Harris County's chief executive officer, explained the decision, saying, "A lot of the projects we're talking about – some of the buyouts [along creeks and tributaries], don't meet the federal government's cost-benefit analysis, so we're going to have to use local funds."

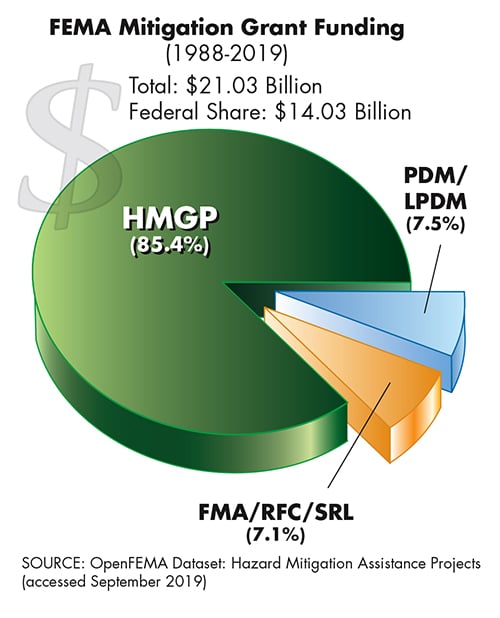

FEMA programs that are available to help implement mitigation projects are described briefly below. Some grant funds become available only after federal disaster declarations. Each grant program has its own rules. In general, communities and some non-profit entities can apply for grants. The types of projects eligible under each program vary somewhat, but generally include floodplain acquisition (buyouts), elevating-in-place, relocating buildings to higher ground, sewer backup protection, and retrofitting dry floodproofing of critical facilities, public buildings and historic buildings. Almost every project requires a non-federal cost share. Importantly, mitigation projects for which communities seek FEMA grant funding must be supported by locally adopted hazard mitigation plans (described in Question 8).

Flood Mitigation Assistance Program. The FMA program provides funding for projects and planning that reduce or eliminate long-term risk of damage to buildings and structures insured under the NFIP. FEMA encourages communities to focus on buildings that have been flooded repetitively and those that have sustained severe repetitive losses, in part by lowering the non-federal cost share. Funding is appropriated by Congress annually.

Success Story Connection

In response to a devastating flood in 2006, Valley View, Ohio, used funds from the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program to elevate nine structures and acquire one property. Since then, the village has participated for several years in the Pre-Disaster Mitigation and Flood Mitigation Assistance programs to fund additional elevations and acquisitions.

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. The HMGP provides funding after major disaster declarations to protect public or private property through various mitigation measures. States have the primary responsibility for prioritizing and selecting proposals submitted by eligible subgrantees, and for administering projects awarded funding. A formula based on the amount of certain types of federal disaster assistance determines the amount of HMGP funding available.

Pre-Disaster Mitigation Grant Program. The PDM program is designed to help states and others reduce overall risk to the population and structures from future hazard events, while also reducing reliance on federal funding in future disasters. This program awards planning and project grants and provides opportunities for raising public awareness about reducing future losses before disaster strikes. Prior to 2019, PDM grants were funded annually by congressional appropriations and awarded on a nationally competitive basis. As of early 2019, FEMA is writing rules to implement a statutory change to the funding level, which allocates 6 percent of total national disaster costs to PDM. The new program has been labeled Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC).

Climate-resilient Mitigation Activities

FEMA provides tools and guidance to help applicants seeking FEMA grant funding to support climate-resilient mitigation activities. Eligible activities include aquifer storage and recovery, floodplain and stream restoration, flood diversion and storage, and green infrastructure. These activities can reduce flood damage and provide ancillary ecosystem benefits, such as drought mitigation and improved water and air quality.

11. How can the FEMA Public Assistance program be used to mitigate future damage?

After events are declared disasters by the president, FEMA Public Assistance funding is provided to state, tribal, territorial and local governments for many purposes, including restoration of public buildings, public utilities, recreational facilities, and roads and bridges. Public Assistance is also provided to qualifying private non-profit entities.

In addition to providing funds for permanent restorative work, the FEMA Public Assistance program can provide funding for mitigation, commonly referred to as Section 406 Mitigation. For damaged buildings, Section 406 funds can cover costs of upgrades to meet building codes and standards, and where codes are not adopted, upgrades that meet the hazard-resistant design provisions (flood, wind, earthquake) of the International Code Council's building codes and the American Society of Civil Engineers' standard ASCE 24, Flood Resistant Design and Construction.

Find out if your community's hazard mitigation plan identifies at-risk public buildings and undersized bridges and culverts. Even some preliminary consideration of what it would take to improve those facilities to better resist future flooding positions your community to work with FEMA to include mitigation in Public Assistance after the next flood. Examples of flood mitigation that can be accomplished, when determined to be feasible and cost-effective, include:

- Retrofit dry floodproofing of buildings and equipment that serves buildings, including pump stations and water treatment facilities

- Relocation of buildings or functions out of flood-prone areas

- Upsizing drainage culverts

- Replacing bridges with wider spans or adding erosion protection to existing bridges

12. What are some examples or types of mitigation actions and projects that we should consider?

Mitigation actions and projects vary greatly – they can be mundane or exciting, expensive or free, complicated and time-consuming or accomplished by changing a policy, regulation or procedure.

Through the mitigation planning process, described in Question 8, communities consider a wide range of possible actions and projects. Mitigation should be focused locally, and the success of your community's efforts to deal with flood hazards should not depend entirely on outside funding. Mitigation that works in your community may be different than what might work elsewhere.

Success Story Connection

Our success stories feature several communities that undertook a variety of flood mitigation projects, such as installing living shorelines, widening river channels, improving bridges, and acquiring or elevating property in harm's way.

The NFIP CRS Coordinator's Manual describes six categories for mitigation actions and projects:

- Preventive activities prevent flood problems from getting worse. The use and development of flood-prone areas is limited through planning, land acquisition or regulation. These activities are usually administered by building, zoning, planning and/or code enforcement offices. Section H describes several higher regulatory standards that fall into this category. Also in this category are open space preservation, stormwater management and drainage system maintenance, and setbacks.

- Property protection activities are usually undertaken by communities or property owners on a building-by-building or parcel basis. You can think of these as actions that move the people away from the flood. The most well-known flood mitigation projects include acquisition (buyouts), elevation of buildings on compliant foundations, relocating buildings to higher ground, sewer backup protection, and retrofit dry floodproofing of critical facilities and public buildings.

- Natural resource protection activities preserve or restore natural areas or the natural functions of floodplain and watershed areas. They may be implemented by a variety of agencies – primarily parks, recreation, and conservation agencies or organizations.

- Emergency services measures are taken immediately before and during an emergency to minimize impacts. These measures are usually the responsibility of city or county emergency management staff and the owners or operators of major or critical facilities. Examples include improved flood warning and pre-planning evacuations.

- Structural projects keep flood waters away from an area using a levee, floodwall, dam, channel modifications or other flood control measure. They are usually designed by engineers and managed or maintained by public works staff. These can be categorized as actions that move the flood away from people.

- Public information activities advise property owners, potential property owners, and visitors about hazards, ways to protect people and property from the hazards, and the natural and beneficial functions of local floodplains. They are usually implemented by a public information office.

13. What should we consider when looking at how some mitigation projects will affect our tax base?

As you contemplate various mitigation projects, you'll need to determine feasibility and effectiveness (does it conform to accepted engineering practices and requirements and is it a long-term or permanent solution) and you'll examine the benefits and costs. Most grant programs that support community-based mitigation projects require evidence that projects are cost-effective, which essentially is a determination that the overall benefits outweigh the costs of implementation. It's usually fairly easy to estimate costs, while identifying benefits is less straightforward.

State Hazard Mitigation Officers and Assistance

Many state hazard mitigation programs provide technical assistance to communities to help identify feasible projects and to develop the documentation to demonstrate cost effectiveness. Grant program guidance is the first place to look. FEMA publishes Hazard Mitigation Assistance Guidance for the grant programs described in Question 10.

Most buyout projects have multiple benefits – and costs – which should be considered:

Effects of climate change on real estate markets.

A study released in early 2019 looked at the value of 2.5 million coastal properties in Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire and Rhode Island and estimated a total of $402 million in lost property value between 2005 and 2017 associated with climate change and location in low-lying, flood-prone areas. When combined with the results of previous studies in 10 other coastal states, losses in housing values could be as high as $15 billion.

- Benefit: Fewer families affected after future floods, reducing the need for public expenditures for evacuations, sheltering and temporary housing.

- Benefit: Repurposing the vacated land for public parks and recreational use, greenways, neighborhood gardens, wetlands mitigation, habitat restoration, stormwater management or reforestation projects. While some of these uses may be more successful when multiple, contiguous parcels are included in the project, some can be implemented on one or two lots. Over the past decade, many studies have looked at the benefits of open space, which, in some cases, adds to the value of nearby properties.

- Cost: Some grant programs require cost-sharing with non-federal funds. Many communities cover local cost-share requirements out of general funds, given the public benefits. Communities with stormwater utility programs may be able to justify using those funds. After damaging floods, sometimes the cost share is covered by the NFIP flood insurance coverage Increased Cost of Compliance (summarized in Question 33), and sometimes property owners agree to buyout offers that are reduced to account for the local cost share.

Success Story Connection

"We proceeded with the buyouts and took those off the tax rolls, but at the same time we were able to create new housing elsewhere that more than offset the losses in property taxes."

– Former Iowa City Mayor Matthew Hayek

- Cost: Questions about how mitigation projects affect a community's tax base usually come up when communities consider buyout projects. Buyouts involve purchasing land, demolishing buildings, and removing paved surfaces to allow the vacated land to serve its floodplain functions. Although buyouts do remove taxable parcels from the tax rolls (see text box), doing nothing in the face of repetitive flooding or recent severe flooding can also cause property values to fall compared to homes on higher ground. Projects to help owners elevate their homes in place keep taxable property, but don't yield the range of benefits of buyouts.

- Cost: Unless a large enough area is bought out to allow termination of utilities and closing roads, public water and sewer service must continue and roads and sidewalks must be maintained.

- Cost: Depending on how the land is repurposed, there may be costs to maintain the vacated parcels by mowing and trash removal.

Must Floodplain Buyouts Decrease Tax Revenue?

Research-based answers to this question were published in 2018 by the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center. The study identified at least four potential strategies to lower the tax burden of buyouts:

- Offering financial incentives for buyout participants to resettle in the same municipality.

- Building new housing developments in non-flood prone areas to accommodate displaced residents and to encourage them to stay in the jurisdiction.

- Maximizing recreational benefits of properties post-buyout to increase local amenities and thus nearby property values.

- Creating comprehensive pre-disaster/hazard mitigation plans that integrate with long-term land-use and adaptation planning to ensure buyouts are part of a strategy that brings value to the community.